Remaking the Land – Ethical Farming & Tourism

Two Sydneysiders have upturned traditions and proved sceptics wrong with an ethical approach to farming and land regeneration, and an award-winning EcoHut to boot

Louise Freckelton and David Bray are custodians of 333 hectares of stunning – yet harsh and fire-prone – land, located on New South Wales’ South Western Slopes bioregion. Now known as Highfield Farm and Woodland, two-thirds of the property falls under an enduring conservation covenant established by the Biodiversity Conservation Trust in 2010.

The area protects critically-endangered box gum grassy woodland, 95 per cent of which has been destroyed or degraded for grazing and cropping. It hosts at least 140 different bird species, such as the critically endangered regent honey-eater and at least 15 bird species that have been classified as vulnerable.The other third hosts a small-scale farming operation, producing award-winning, native-grass-fed dorper lamb, but also offering beef, chicken, eggs and more, as well as their award-winning off-grid and offline EcoHut, Kestrel Nest.

Ten years ago, Louise and David were inner-city ‘greenies’, erudite employees of the University of Sydney, with not a pinch of farming experience between them. It was their passion for high country hiking, however, that attracted them to environmentalism. That, and budding interests in botany (in Louise’s case) and birdwatching (in David’s case). When the opportunity arose to purchase a piece of land in their beloved Snowy Valleys, they dove head first into the world of sustainable agriculture. When it comes to farming, Louise and David have stayed true to their greenie roots, eschewing traditional practices in favour of a well-informed conglomeration of frameworks that advocate regenerative, ethical and holistic management of the land.

Rather than cling to dogma though, their approach was highly intuitive and led by their personal ethics. Terms and frameworks like ‘regenerative agriculture’ and ‘permaculture’ were meticulously studied, tested, and then applied only where it made sense for their land, and their mission. And their mission? To heal their land by revegetating paddocks, restoring native pastures, increasing biodiversity, sequestering carbon and raising healthy and happy animals, all in striving to do their part tackling the climate and biodiversity crises.

“For us ‘regenerative farming’ is necessary but not sufficient, for instance, you can graze regeneratively and still have massive food miles on your product. You can graze regeneratively and still not use pain relief when removing tails or castrating,” said Louise.

Consulting the ‘experts’ hasn’t always allowed for nuance – they were once told by an agronomist to destroy their endangered ecological carex sedgelands because “your sheep won’t eat it”. Or, to cut down their ancient eucalypts to “do your zones properly” by a permaculture expert. Instead, their approach has been unfaltering and multi frontal, led by an intimate understanding of the subtle differences between a struggling and a thriving ecosystem.

Active revegetation has been a priority on the farm, by regularly planting endemic species such as Blakely’s red gums, red box and yellow box. Known as paddock trees, these serve an important function in the ecosystem by creating a wildlife corridor for biodiversity. Research has shown that by 2060, all the remaining ancient paddock trees will be dead, making this type ofsuccession planning indispensable.

By managing weeds through time-controlled grazing, diligent observation and botanical know-how, they’ve also seen substantial expansion of native grasses such as kangaroo grass (Themeda triandra), weeping grass (Microlaena stipoides), wallabygrass (Austrodanthonia) and red-leg (Bothriochloa macra). More than tripling the amount of paddocks on the farm – from four to 14 – has helped with this, and has reduced topsoil erosion on sheep-trafficked hilltops.

Contrary to popular opinion that grazing their South African dorper sheep on native pasture would see them ‘run to fat’, their dorper lamb has won the Delicious Produce Awards two years in a row – in 2020 they were awarded the National Gold Medal.

David and Louise are committed not only to regenerating their farm, but supporting the regional communities that surround them by supplying them as a priority, rather than shipping their produce off to the cities. This also contributes to low food miles, which are key to reducing their carbon footprint.

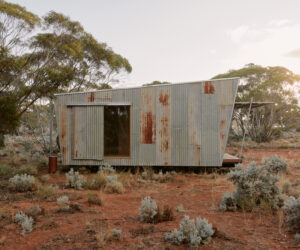

Their EcoHut, Kestrel Nest, has also contributed to their community, becoming a tourist destination in itself. As a finalist in the 2022 National Banksia Award for Sustainable Tourism, this impeccably-styled hut is turning heads, now fully-booked most weekends, allowing guests to experience off-grid living in luxury.Perhaps one of the most striking things about the way David and Louise farm is their patient observation and nurturing of their land, perfectly captured in the Wiradjuri word ‘yindyamarra’– fitting given that Highfield sits on the ancestral lands of the Wiradjuri Nation – meaning to take responsibility, to be patient and go slowly, and to listen and respect, a sentiment that this fragile planet so desperately needs more of if we’re to pull through the coming decades.