Reimagining Indigenous social housing

Aboriginal Housing Victoria, Australia’s largest registered Aboriginal Housing Agency, has teamed up with ClarkeHopkinsClarke Architects and Indigenous landscape designer Charles Solomon to transform ageing units on a 1000-square-metre site in suburban Dandenong as part of its first moves into multi-residential apartment development. Funded as part of the Victoria Government’s $2.7 billion Building Works package and fast-tracked through planning recently, the project creates 10 much-needed one- and two-bedroom homes for diverse tenants and reimagines the connection to culture and Country possible in urban social housing settings.

AHV currently manages more than 1500 rental properties for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in Victoria – mostly larger villas and houses, for which singles, couples and younger people often don’t qualify. “There’s a severe shortage of one- and two-bedroom units, not just for Aboriginal tenants but right across the social and community housing sector,” says AHV CEO Darren Smith. “We have some coops and some Aboriginal housing within apartment buildings, but these will be the first medium density apartments developed specifically for Aboriginal tenants.”

“The younger generation in particular is really struggling for access to social housing because they don’t meet the criteria to apply for the majority of housing stock,” Darren says. “They’re left more or less to a private rental market that discriminates, or they’re at high risk of becoming homeless.” Although Aboriginal people make up just one per cent of Victoria’s total population, 18 per cent are either recurrent users of homelessness services or at risk of homelessness. “To be over-represented to that level in homelessness services is a really confronting statistic. This is one of the ways we see to help to address that.”

AHV is currently working with Breathe Architecture on an apartment development in Melbourne’s inner-north, and Darren says more may follow “especially in the major centres and metropolitan Melbourne”. “The need for Aboriginal-specific housing – safe, secure and culturally appropriate – is really high within the major centres and particularly in Melbourne,” he says. “The challenge, which no one’s surprised about, is access to land and opportunity.”

“Huge towers with 150 tenants is not what we’re trying to achieve. We want to improve our tenants’ quality of life, offer opportunities for them to improve their lives, and provide a solid home base to start that from. We want to create homes the Aboriginal community is proud of. To some degree we’re taking a bit of a risk because it’s out of the norm for Aboriginal housing. We’re really stepping that up and looking to the future and saying, ‘How do we address a need that far outweighs the availability of land?’”

AHV’s brief to ClarkeHopkinsClarke Architects, whose social housing projects include a series award-winning apartment developments for Women’s Housing Limited, was multi-faceted. Like all the best contemporary social housing this development needs to be high-quality, robust, extremely energy efficient, low-maintenance, safe and secure, well suited to its streetscape, and a source of pride for both tenants and neighbours, helping to create community connections and eliminate stigma traditionally associated with older-style social housing. It must be flexible enough to accommodate a wide range of tenants over its lifespan, including young professionals, couples and small families. Crucially, says Darren, it must also reflect AHV’s Indigenous design principles and “speak to Aboriginal culture and connection to Country”.

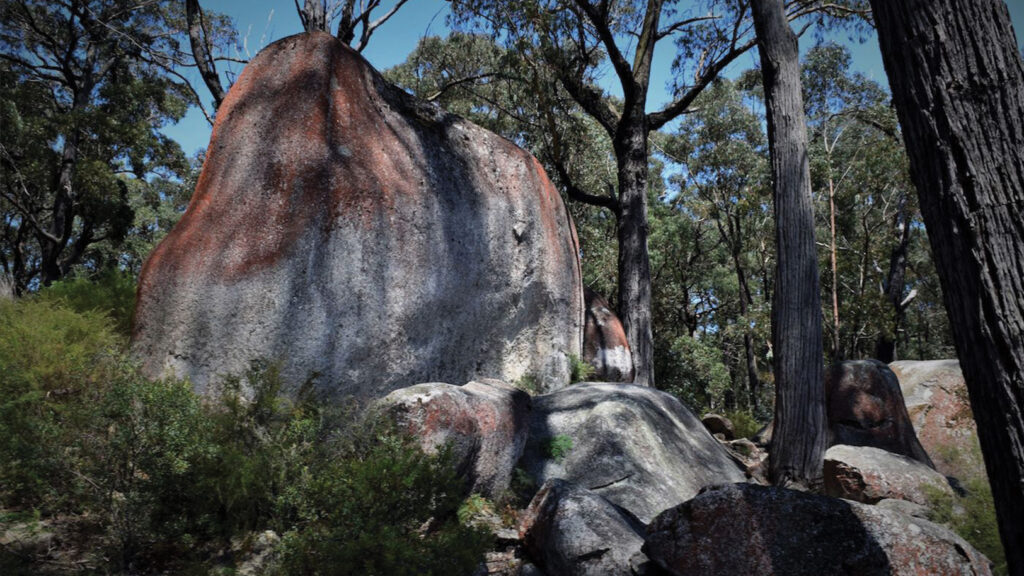

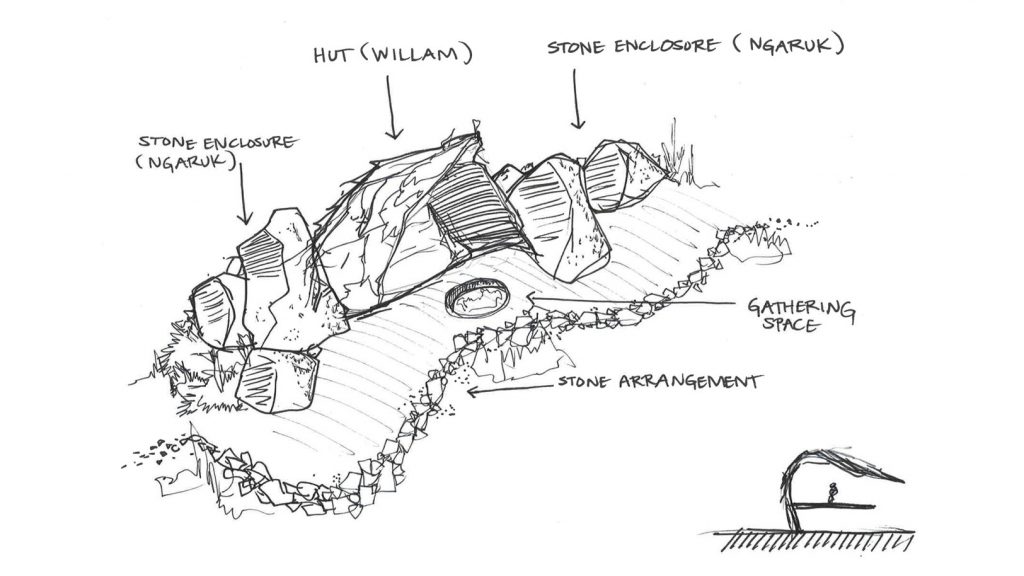

Indigenous architect James Gilliland drew design inspiration from the culture and Country of the Ngaruk Willam people. “Ngaruk is stone and Willam translates roughly as hut, and the anchoring concept relates to the Ngaruk Willam clan as stone dwellers,” he says. “We selected materials that reference local stone and designed a built form inspired by temporary shelters, Mia Mia, used for seasonal harvesting. We’ve translated the curves of the Mia Mia into the sweeping roof form over the loft apartments. This creates the appearance of a townhouse typology from the street, which was important in helping to integrate the development into the streetscape.”

“These are quite literal interpretations of simple ideas, but they created a strong narrative that AHV responded to. We worked closely with Indigenous landscape designer Charles Solomon and AHV’s Nicky McNamara to extend that into a holistic narrative that integrates landscape and built form, which really resonated with the client,” James says. “Charles, Nicky and some landscape design students she worked with at RMIT have put lots of rigorous thinking and research into every element. Plants are selected for their symbolic meanings and traditional uses in medicine and tools. There’s lots of granite and volcanic boulders in the area so that’s referenced in Gabion stone walls at the front of the building and rock features in the communal garden. The landscape can be used by tenants as a cultural learning tool as well as a beautiful shared space. The centrality of Indigenous landscaping in this project is really unusual for social housing, and it’s been a big part of winning over tenants to the idea of apartment living.”

A larger two-bedroom Elder residence near the front entrance is another distinctive feature. “Elders are very, very highly respected in the Aboriginal community so it’s normal practice to go the extra mile to provide something Elder-specific,” Darren says. “By positioning them near the ground floor entrance they have the opportunity to welcome people and be a first point of contact as you come into the building. Even if it’s occupied by a single Elder it’s important to provide space for family or others to come stay, and a large enough kitchen-dining area for them to have a cuppa and a yarn with people.”

ClarkeHopkinsClarke Architects’ Multi-residential Partner Toby Lauchlan describes the project as an exciting, hardworking, sustainable new model for Indigenous social housing. “It’s quite an experimental model, and it incorporates so many elements and connections to Country, but it’s also a really lovely, compact, high- ESD development,” he says. “There’s lots of natural light, ventilation, highlight windows, PV panels, and rainwater tanks to maintain beautiful landscaping. We’ve incorporated a secure private front entrance (so tenants control who comes in and out), the Elder residence, two one-bedroom apartments overlooking the street, and two-bedroom, double-storey loft-style apartments with large terraces to the rear. All link visually and physically to the beautiful central communal garden. There are no lifts, just lovely open stairs and winding paths through the landscape.”

“Our team has drawn on learnings from quite diverse social and affordable housing projects we’re working on, from townhouse-style apartment developments to key worker housing, co-living studio apartments in converted pubs and contemporary rooming houses. They all share a need for very high quality, robust, sustainable homes that tenants love, in great locations where they can access all the amenities they need and connect with local communities.”

Darren says the unusual design won over tenants initially wary of apartment living. “Typically, a social housing development doesn’t focus on landscape or connection to outdoor space,” he says. “So for tenants to be able to walk around even a compact garden and get in touch with nature in this sort of development is a really great opportunity. These are Aboriginal homes, not just rental apartments. They bring indoor and outdoor spaces together to tie into that idea of connection to Country. What we’ve achieved on a site this size – I think it’s really quite impressive. When we first started talking with tenants about our plans everyone wanted a house that was big and roomy and gave them a sense of space. By the end we had people saying, ‘Wow, if this is what you’re going to provide I really would like to live in it’.”