Interwoven

Spain’s Alvaro Catalán de Ocón recalls the creative journey shared by the PET Lamp project and the Northern Territory’s Ramingining weavers that culminated in an installation for the NGV Triennial.

Founded in 2011, the PET Lamp project has taken Spanish designer Alvaro Catalán de Ocón and his co-designers to South America, Africa and Asia, where they have worked with communities of artisans establishing a market for lamps made through the merging of discarded PET bottles with traditional weaving techniques.

Catalán de Ocón has recently returned to Australia for the launch of the Triennial exhibition at the NGV and to see the results of his latest collaboration on display. Despite the effects of a long haul flight, his enthusiasm and wonder at the creativity of the Ramingining weavers of the Northern Territory is palpable.

During the summer of 2016 Catalán de Ocón spent six weeks working beside nine weavers to create the latest iteration of the PET Lamp project, a commission by the NGV. “For the first time we were working on an installation rather than a commercial proposition; it was like storytelling over six weeks which ended up in one special piece.”

“With all of the communities we work with the word ‘waste’ does not exist in their language – something is simply in the wrong place, so a plastic bottle doesn’t find a place in their system, so we try to give a place to that waste,” explains Catalán de Ocón. “In this case the bottle makes the perfect sense in solving the problem of housing the electricals.”

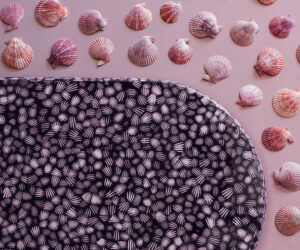

The Ramingining weavers embraced the concept right from the beginning and began working on their own individual lampshades, creating round figures based on their traditional mats. One of the weavers, Mary Dhapalany Madhalpuy, created two pieces instead of one and then connected the two to signify her being a twin sister to David Gulpilil. This became a source of inspiration for creating new bonds and Catalán de Ocón and his team began to explore the rich universe of Indigenous Australian relationships and topography.

“It shocked me how open this community was, considering their history of weaving; we arrive with a plastic bottle and they embrace it; it was amazing how open-minded and flexible they were.”

“In fact, flexibility was key to the successful collaboration,” says Catalán de Ocón. “We needed the time to adapt to their ways, communication was very special, you feel like you are really in another reality. It was more metaphorical and open to interpretation. Even with an interpreter it took a while for us to adapt and understand the rhythm of time. One day they might say ‘we have a funeral’ and leave and we would not know how long that would take, hours or days.”

Living and working with the community for six weeks allowed time for this rhythm to be established and the worked evolved from there.

The finished work of Mary and her co-weavers, currently hanging from the ceiling at the NGV, is a magnificent, expansive piece of group work, complex and rich, “like a family tree mixed with an interpretation of the landscape,” explains Catalán de Ocón.