Great Minds

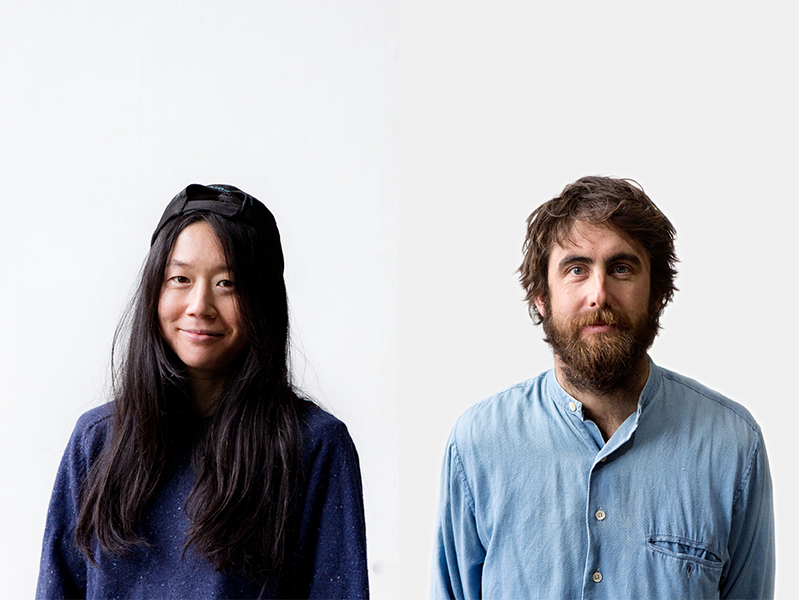

Makiko Ryujin and Michael Gittings are makers and collaborators who bring out the best in each other.

This might sound controversial, but not all great minds think alike. In the case of Makiko Ryujin and Michael Gittings, their differences are what makes theirs such a prosperous partnership.

Makiko saw much of the world before coming to Melbourne. Born in Japan, she spent a year studying in Jakarta before finishing her secondary studies in Melbourne, where she later completed a Bachelor of Photography degree at RMIT University. A while later came Makiko’s foray into woodturning, which lead to a fateful stint at Coburg coworking space, Space Tank Studio. It was here that she crossed paths with Australian artist, Michael Gittings.

The two’s 2019 collaborative work, Impermanence, is what Michael refers to as “the seed for the evolution of our work together.” It’s a fitting metaphor, given that Makiko and Michael’s newest project for the NGV Triennial, Samsara, takes the form of a tree. The two-part lighting sculpture work is composed of a textured steel trunk and opens into a canopy of branches fabricated by Michael, decorated with Makiko’s charred timber light shades with flourishes of gold leaf, upon which rest glowing handblown glass bulbs.

“With the year that we have had, Samsara has been a little ray of hope to work on each day,” Michael reflects. “It is a joy to work alongside Makiko as our different styles and knowledge bases complement each other well.”

Samsara is where the two makers’ walks of life meet, but do not merge. Michael’s working background in construction and expertise in metalwork is apparent, as is Makiko’s finesse of charred timber – a material recalling her Japanese childhood.

“… Putting together all the parts [is] always the exciting part of our process. Lots of wows!” Makiko shares. They worked separately on Samsara from their shared studio in Fawkner, combining Michael’s big-picture approach with Makiko’s eye for fine details.

It’s her eye that finds beauty in life’s smaller moments. Makiko lists pebbles, rust and signs of age as sources of artistic inspiration. In particular, she describes the wrinkled hands of a hardworking older neighbour as one might a muse.

Makiko considers the impact of her woodturning on the environment and sources her timber from the roadside or arborists. She excitedly points out that even the wood shavings are reused in her garden and offcuts find new purpose as firewood. “I think about sustainability as a cycle of life, and being kind to the natural environment,” Makiko notes. “When I use [these] trees, I feel responsible [for] any of my offcuts and woodshavings. [They are] used or get back to the cycle of life again.”

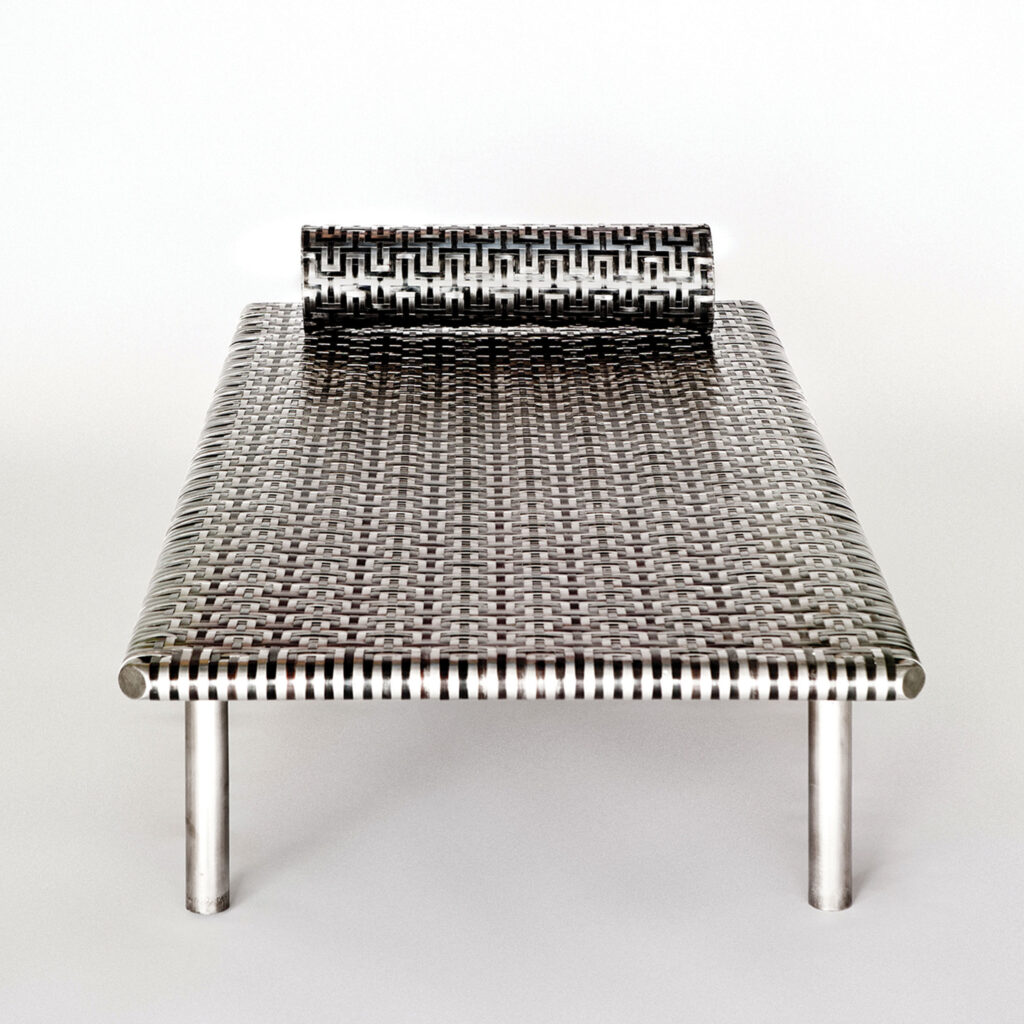

For Michael, sustainability means creating work that withstands the tests of time and taste. He explains: “In my work I try to use, where possible, metals with high makeup of recycled material and utilise low-cost manual techniques. I want to create low-volume, high quality heirloom pieces that don’t further the ideas of mass-produced works.”