Evolutionary

Architect Ben Daly spared no time, effort or thought when it came to carefully restoring a New Zealand railway cottage.

Beneath the humble hip roof of this railway cottage, there’s a lot of thought. Architect Ben Daly and his wife Dulia bought it unexpectedly in a rural valley north-west of Napier in New Zealand – “Dulia insisted we drive out to the countryside; we didn’t think much of the home when we first saw it” – and only paused for a two-minute consideration before they put in an offer. The minute they owned it, Ben’s mind began ticking over.

He thought not about how to ‘renovate’ the 80-square-metre Hawke’s Bay home they’d bought for less than $200 000 – he shuns that word anyway – it was a far bolder test, one that involved examining what an ‘architect’ actually does, before the first nail was levered from the boards.

Ben’s friend, artist Martin Poppelwell, became a sounding board in the process of making their own this 1950s cottage, once used as accommodation for railway workers on the line from Napier to Gisborne. “Architecture can be quite a lineal progression – you study, do a set number of years in the workforce, become registered – and somewhere in those years, all the whimsical things you were taught at uni go out the window. I don’t sit anywhere on that line anymore. With Martin, I’ve learned that it is by questioning that you progress. Now I’m on an outer rim and happy with that awkward balance between the technical and artistic side of my job.”

Built of rimu and produced, cookie-cutter fashion, from a set of drawings that was repeated wherever the railway ran, the cottage was unadulterated with three bedrooms wedged into the rectangle and a level of wear and tear that 60 years of existence in an isolated environment brings.

For Ben, there was no question that he’d work within the footprint and repurpose available materials. “I didn’t want to remove the social history; it has a right to be there and if you can draw from it, there is a whole narrative to be explored.”

The dwelling was oriented for sun with morning light filtering into the kitchen and living spaces throughout the day, but the layout of the rooms was ripe for change. “These houses are an adaptable species,” says Ben. He didn’t want to demolish or extend. He did want to make something beautiful and personal.

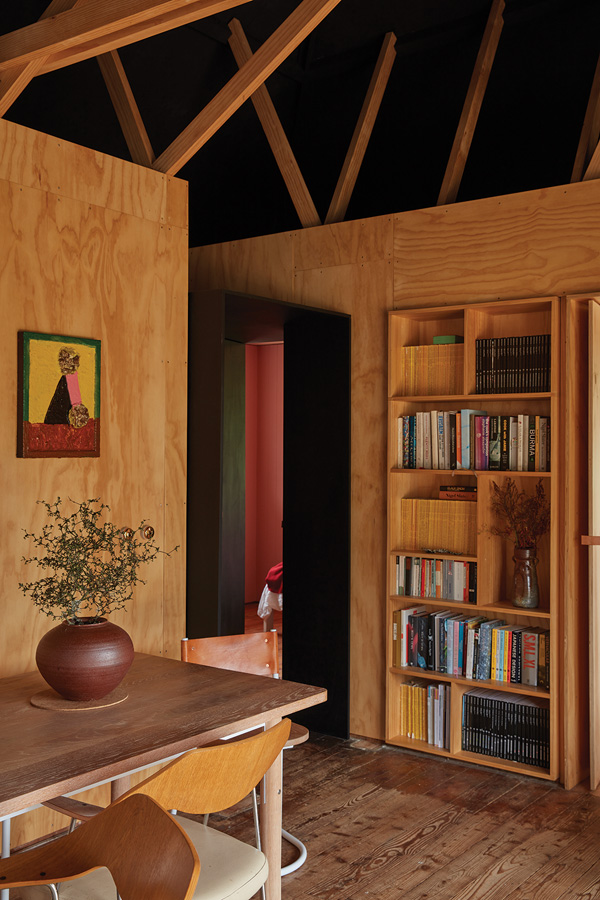

The couple lived in the home with Dulia, an orthopaedic registrar, heading to work to support the project, and Ben putting his time and care into every layer. “It was important to be engaging with the house so we were comfortable with every step.” On sunny mornings, he’d take his coffee out to the garden and contemplate the next move. The idea of removing the flat ceiling to use the capacity beneath the roof came on just such an occasion – “Volume is such a powerful tool”. In an interesting experiment, the underside of roof was painted black to absorb light. New exposed pine trusses are lighter beams within the darkness.

Beneath the high pitch, selected walls were dismantled while plywood insertions created an entry cubicle (cave-like in black), sleeping and bathroom pods. A massive concrete-and-brick fireplace was taken out. “When that went, the space started to breathe.”

Apart from conceptualising the changes, Ben was doing most of the work. Such “slow architecture” takes time and over three years, he was not idle. As a trained architect, not a builder, some tasks were challenging for him. “But I thought about them – and backed myself.” He ended up making both doors and doorways – he calls them cowls. “They’re deep and slightly lower so there’s a sense of being encased, like walking through an archway.” He handcrafted anything he could. “I’d sit and think: ‘I have timber, so how can I make window frames?’” The key was to not aim for perfection. So what if the edges didn’t meet perfectly? He repurposed rimu from the original kitchen into units and made benchtops from beams from an old factory. “The nail-heads and holes are still there so it reads as old.”

Throughout it all, he kept an eye on minimising waste. “I only went to the tip once or twice over the entire project.” He was horrified, when he pulled off the original ceiling, to discover that the ceiling was set above the height of a standard sheet of wall lining. “Eliminating waste through design has always been an important part of my process.”

The jigsaw pattern that was left on the floor after all the pulling apart and putting together was due for a sand and a stain, before he thought some more. “You could see where previous owners used to walk through the space. The Douglas fir was worn into ridges and tactile when you ran your hand over it.” He decided to leave it well alone.

For Ben, it is this engagement (physical, mental and spiritual) with a house that makes it special. He had lived in London, Sydney and Wellington, so the rural environment tested his resolve. Water from the bore was laced with heavy metals – “If you left it to sit in a cup it would turn yellow” – and the vegetable garden failed to thrive in the parched climate. Engagement with these aspects, too, became part of the story; two new rainwater tanks are not buried but in full view. “I didn’t want to hide them. It’s a good way to understand how water flows from the roof into pipes that link to guttering and a filter system.”

Although Dulia’s ongoing orthopaedic training has called the Dalys to move to Christchurch, they have not sold. This home has given Ben more insight into a profession that he feels may have otherwise lost its way, as well as a chance to re-engage with the craft of architecture. “My philosophy now is that you shouldn’t be able to design something if you don’t know how to put it together.”

Throughout it all he held on to Poppelwell’s musings: time is your tool. The cottage, once in danger of going the way of its fellows, is here – history intact, future secured.

Specs

Architect

Palace Electric

palaceelectric.com

Passive energy design

The railway cottage is oriented to the north, with the main living, kitchen and main bedroom orientated to make best use of the sun’s path. Roof overhangs provide shelter from the summer sun whilst the living room and kitchen façade have large openings to allow for the deep penetration of the sun and warmth into the main space.

Materials

Careful consideration has been given to the list of building materials used throughout the project. All the new building work can be seen as a palette of locally sourced timbers/plywood linings. All trims have been removed to express clean joints and all fixings exposed. All hardware to doors has been constructed from simple materials that were at hand, and doors themselves from single sheets of plywood. The joinery was made from either salvaged timber from demolition sites or from the original 1950s joinery that was carefully taken apart, resized and sanded, then turned back into new forms of joinery. The windows were made from a combination of old window frames with inserts of new timbers where needed. All paints are Resene and are all low-VOC. All timbers are oiled using WOCA natural oils.

Flooring

There is a combination of flooring types. The main floor throughout is still the original Douglas fir timber floor from the 1950s and remains unfinished with its original patina. Where walls have been either removed or sections of the floor replaced, new rimu floor has been used. This was either from tongue-and-groove boards that have been made from old structural beams or are from old joinery panels that came out of the cottage.

Heating and cooling

The large glazing to the northern side captures the sun and heat of the day, while overhangs to the roof provide shade in the winter time. A small wood burner is the only heating source needed for the space for the wintertime. The high and open volume of space traps the heat up high in the main living space and cross ventilation is enough to cool the space down when required.

Water tanks

Rainwater from the roof areas is collected into a 20 000-litre partially buried tank, which provides water for toilet flushing, washing machine and household tasks. A smaller 2000-litre tank also collects rainwater for use in the vegetable beds. An old bore hole is also utilised and provides year-round irrigation for the entire site.

Reuse and waste

One of the main features of the project was the reuse of materials and careful consideration of building waste from building products. All building timber that had been removed from the project made its way back into the job by some means, either as furniture, door hardware, window and kitchen/living room joinery.

Sustainable building

When designing and building, all building products were sourced locally from locally grown or made products and companies. Certain materials have even been used in their rough band-sawn state. This has helped to limit the embodied energy in the materials themselves and their construction. One of the continuing exercises in the reduction of waste comes through thoughtful design, trying to eliminate cuts and waste. Any waste that is created must then have a secondary use.