Spiritual Puzzle

The clean, pared-back lines of this new family home belie the knotty problem- solving that went into its design.

The little known ideologies of Sthapatya Veda architecture incorporate elements of passive solar design. This was fortunate for Peta and Joe Davy because it meant, when it came to building their home, the Auckland couple could both stick to their guns. Peta grew up with a father who was “a greenie” and inherited his passion to step lightly on the land. Jo, on the other hand, practises Transcendental Meditation, so his response was driven by the teachings of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, founder of the movement and one-time spiritual guru to The Beatles. While planning this house in the South Auckland suburb of Mangere Bridge, the two had to meet in the middle.

Visitors to the home in its unassuming cul-de-sac initially notice the remarkable geometrical strength of its outline. “The shape loosely mimics that of Mangere Mountain,” says Peta. A butterfly roof acts as a counterpoint to the heft of the form below.

Inside, a sense of spaciousness is the first impression, but those who are more eagle-eyed might spot a “flaw” in the floor. A few steps beyond the entrance a square of timber planks is placed at right angles to the rest. “It looks like a trapdoor, but it’s actually the Brahmasthan which marks the central axis of the house,” explains Peta. Some Vedic architectural texts suggest the Brahmasthan serves as the silent core and should never be walked on. In a home shared with two growing boys – Andy (10) and Sam (7) – that could be true. It’s far more likely to be scooted over at a blistering pace.

The couple bought the property, and the worse-for-wear 1970s house that was on it, as a rental investment. It wasn’t long before the location won them over and they decided to take up residence. At its northern end, it overlooks the green hillocks of the Lost Gardens, a protected area of spiritual significance. Remnants of stone mounds indicate it was once used by Maori for gardening. In the distance, across the Manukau Harbour, Hillsborough ridge rises on the horizon. The original home was sold for NZ$10,000 and transported north to become a bach.

Peta has worked with her mother as a designer at Yellowfox for seven years. She says she is saddened that her clients seldom use sustainability as a yardstick. “My father always said that you must lead by example,” she explains, so the house was her chance to practise her principles.

Keeping within the parameters of Sthapatya Veda could have been onerous. This ancient science strives to respect cosmic energy lines and proponents believe that if this is adhered to, a building will promote harmony, health and wealth. Peta, who worked in collaboration with Vedic consultant Neil Hamil and architectural designer Mark McLeay, likens the process to doing a jigsaw puzzle blindfolded. “Yet solving all those problems was very fulfilling,” she says.

One edict states that the orientation of a dwelling has a dramatic impact upon the quality of life of its occupants. In terms of spatial design, the dictum was that the toilets and sinks face north. Cooking was to be done in the east since when the sun rises its energy is at its most nourishing. In addition, the dimensions of all the rooms were prescribed to the last millimetre, reflecting the idea that proportion is the key to successful design in nature.

Overlaying all this are Peta’s own eco-conscious sensibilities. Concrete floors to the north, combined with a roof pitch that captures every last drop of winter sun, means the wetback fireplace is used to supplement water heating, rather than to warm the house. The angle of the butterfly roof allows solar panels on the rear bedroom wing to power the hot-water system.

“All four of us shower in the morning and there’s more than enough warmth to last.” Insulation is compacted into the 220 mm- thick walls and the double-glazing works almost too well. “Thank goodness for the high louvre windows – the house would be a hotbox if we had to shut it up completely during the day.”

An important component of Sthapatya Veda architecture is building with natural, non-toxic materials suitable to the local climatic conditions. In the Davy’s case this was easily done. “Joe’s family runs a timber recycling business,” says Peta. “So we were always going to use secondhand timbers.”

Nevertheless, she was adamant that the aesthetic should steer clear of the rustic look. Her penchant is for Scandinavian simplicity, with a bit of everyday messiness thrown in.

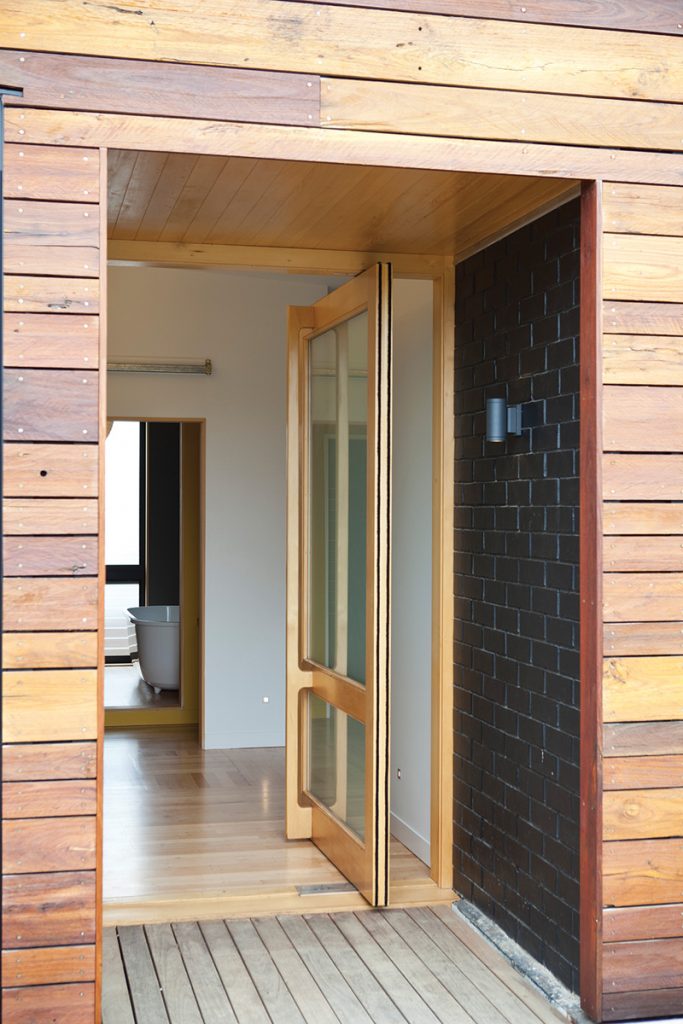

The house was conceived as a black brick box, protected by a timber shield – a striking wooden coat made from recycled power poles. “There aren’t many people who could live with its imperfections.” Spiders and insect life find homes in the hidey holes that pock-mark the cladding’s surface. And Peta proves her devotion by oiling a section of the timber skin every weekend. “I love its colour and don’t want it to fade to grey.”

Yellow-wood soffits are in keeping with her love of richly hued timbers while inside, honey-toned tawa, once in a 1950s house in East Auckland, has been repurposed as flooring, walls and on the sliding doors. The slim-line planks may not be en vogue, but they bring a fine elegance to the narrow 162-square-metre home.

Rescuing the unwanted and unloved is Peta’s modus operandi for keeping the budget under control, and she’s not averse to asking suppliers for cast-offs. Case in point: the veneer that now coats the kitchen cabinetry. “The company had these leaves lying around out the back for twelve years!” The Japanese aesthetic of the veneer is set against a black backdrop to emphasise its colour and interlocked grain.

Another example is the bricks that anchor the north and south ends and feature on the fireplace. These were seconds that sported a “hideous yellow rumbled surface”. Peta always knew she was going to paint them white so she asked the bricklayer to turn their faces inwards as he laid them.

Melding two philosophies into the dwelling has taken compromise, but it has been worth it. “We’ve ended up with a home that feels very grounded and linked to the environment.” The children walk to the local school across the paddocks of the Lost Garden, passing grazing sheep and cows. At one point in the year the ruminants must share the field with about 2000 oyster-catcher birds who come to breed here.

The family feels the privilege of being in such a special place so close to the city. A pencil drawing tacked to the wall behind the dining table says it best. On it seven-year-old Sam has written: “This is our house. I love our house. We are lucky.”

Specs

Architect

Creative Arch Auckland NZ

creativearch.co.nz

Spatial planning and interiors

Yellowfox

yellowfox.co.nz

Builder

Mark Waller of Waller Projects

Passive energy design

The house runs exactly north–south with glazing open to the views on the north end. In winter the sun penetrates well inside the living area, warming the concrete floor. Louvre windows at each end of the home create cross-flow ventilation. The design provides comfortable living with low energy use year-round.

Materials

The north end exposes the concrete slab, clear sealed and saw cut for improved thermal mass. The cladding consists of a plywood base, with an outer “shield” of recycled power poles to the east and west elevations; north and south consist of painted brick seconds. The main volumes are of highly insulated, lightweight, mainly timber framed construction, with limited steel. The interiors feature recycled power poles to kitchen island top and dining table, recycled NZ tawa to sliding doors and timber walls. Resene Paints are low VOC. Recycled kauri is used to create the children’s floating bunk bed, and reclaimed oak to the bathroom and ensuite vanity shelves. Kitchen cabinets are built from low formaldehyde melamine and veneer. A stainless steel back bench creates an indestructible work surface. All timber supplied by Kauri Warehouse.

Flooring

The clear-sealed concrete floor slab is saw cut inlaid with beach glass the children have collected over the years. Timber floors are narrow board recycled NZ tawa. Bedrooms are covered in 100% felted NZ wool carpet.

Insulation

The roof and external walls are insulated with fibreglass, interiors walls are insulated with reclaimed wool insulation from a demolition project.

Glazing

Windows, double-glazed, are powder-coated aluminum and yellow cedar timber frames.

Heating and cooling

Effective cross ventilation through the home eliminates the need for electrical cooling. The wetback wood burner provides heat and hot water through the winter months.

Hot water system

Hot water is provided by solar hot water system in the summer and the wood burning wetback fireplace in the winter when sun can be scarce.

Water tanks

Rainwater from the roof is directed to a slim 5000-litre above ground tank, which provides water for toilet flushing, washing machine and garden irrigation.

Lighting

Low-energy LED and fluoro lighting with no in-ceiling downlights to disrupt ceiling insulation. Fluoro tubes run hidden along the top of kitchen and bathroom cabinetry, and along a pelmet in the hall to create a up-lit glow to the spaces.