Setting Up Camp

In a forest outside Bendigo in central Victoria, where temperatures swing from freezing winters to scorching summers, a local architect has used lessons learned during a stint in Brisbane to conceive and build a compact, affordable “camp” for his young family.

On a chilly late-winter day in Junortoun, 10 minutes east of Bendigo, it’s hard to believe that many of the design ideas integral to the new home of local architect Lucas Hodgens, an Associate at e+ architecture in Bendigo, hail from the delightfully and consistently temperate climate of southern Queensland. Lucas and his partner Naomi grew up in Bendigo but moved to Brisbane around eight years ago to study and work in a completely different environment. Lucas was a former stonemason with plenty of experience building thermally snug stone and mud brick houses capable of closing down to withstand the dramatic seasonal variations in temperature that are par for the course in central Victoria. He found great delight in making the leap to architecture in a region where thermal comfort depends on openness rather than closure.

“My interest in architecture really came from that notion of mass, and thermal mass, and solid walls with openings in the walls,” Lucas recalls. “That was part of the reason why I wanted to move to Brisbane to do my architectural study, because it would take me out of that comfort zone. Up there it was a complete opposite challenge. The houses we were designing there were like a veranda. It was all about being open most of the time but then closing down when you really had to … to protect yourself from the rain, or (when) it was a really windy day. Even our office we built there – because we did building projects as well – didn’t have walls. Even though we were sitting there working on computers and drawing boards, we only had a curtain protecting us from the outside. It was such a beautiful way of living, I just miss it so much.”

When Lucas and Naomi returned home five years later they were keen to start a family and build their own home as inexpensively as possible using design principles they had embraced up north, adapted to local conditions. This was no easy task in a region where temperatures can veer from two degrees in winter to 45 degrees in summer.

“That’s the beauty of doing your own house,” he says. “I wouldn’t do that for a client. This has really been about us coming back and bringing a little bit of Queensland with us. And we love it, but it’s definitely not for everyone.”

Happily, finding a site surrounded by family – and the bush they loved – was a cinch. Naomi’s parents had moved into Bendigo some years back from a 10-hectare bush block in Junortoun, which they’d retained to sub-divide for their children. They carved out 10 one-hectare allotments, retained half for family and sold the rest. Each one was given a designated building envelope of 50 square metres, beyond which the owners couldn’t clear.

“The CFA (Country Fire Authority) and the DSE (Department of Sustainability and Environment) did a land capability assessment,” Lucas says. “Basically what we said was we want to protect as much of the bush as we can, and we obviously want to protect people from bushfires. This was before Black Saturday – the laws are more stringent now. So (we) took a 50-metre by 50-metre perimeter fence and fenced all the blocks before people bought them, and that was the designated building envelope. That was clear. Anything outside of that was natural bushland, and it was to remain bushland, untouched.”

The devastating bushfires that ravaged the Bendigo region in February 2009 had a profound influence on the home Lucas designed on the block he and Naomi chose, and which Lucas built over 18 months of evening and weekend work around his day job at e+ architecture. “We got caught out a little bit, the fires happened during our design process, and we went from what was considered a medium fire risk to a high fire risk because they changed the bushfire attack level system,” Lucas says.

Plans for spotted gum cladding, a timber deck and timber window frames, chosen because they’d weather beautifully into the site, had to be scrapped. “We nearly completely scrapped the design,” Lucas recalls. But their compromise solution turned out to be a highlight of the place for both of them. “We took the value of the timber, which was about $40,000, and put copper on the roof,” Lucas says. “That for us means that because you look down on the house it still weathers and sits (comfortably) in its site.”

The house that emerged is essentially a central, pitch-roofed living pavilion that opens north to the elements via extensive glazing and screening and is bounded in each corner by an adaptable flat-roofed pod or box. Currently these four spaces function as a master bedroom, shared children’s room, home office and playroom/TV room, but they’re designed to adapt over time to the family’s changing needs. At 5.4 x 4.5 metres each they’re generous spaces in a house that measures just 160 square metres in total, or about half the Australian average.

Critically, these rooms offer not only a sense of privacy and retreat from the main living area but opportunities for air movement via high level louvre windows and, opposite, full height openings to the surrounding landscape. Unlike the central pavilion, elevated for access in case of bushfire, the boxes sit low to the ground on concrete slabs and are accessed from the living area via

a couple of sunken stairs. Externally the pods partially tuck under the copper-clad pitched roof, blending into their surroundings and creating natural courtyards in the negative space between them, which Lucas says helps to compartmentalise the unstructured bush beyond. Glazing creates a strong sense of connection between inside and out, and the generous scale means they can be put to various uses as children Harper and Audrey grow, without the need for an extension.

“We love open plan for living but we also like being able to retreat,” Lucas says of the straightforward structure. “And we also loved the notion of – (because) this is where we used to come out and camp – setting it up as you would a camp site. We wanted this central space to be more like an outdoor space that we could close down for shelter and comfort, but we wanted it to be as transparent and outdoor as possible. That’s why all the furniture in here is loose, including the kitchen – it allows us to change it to suit. If you come here in summer we have the furniture orientated differently because the wood fire becomes obsolete. We’ve got a big swing we hang from the rafters – we have all the glass stacked back into the recesses and have the security screens across – and venetian blinds on the outside of that, so the sun doesn’t come in. We really just rely on passive means – cross ventilation and the wood fire and ceiling fans – to keep us cool and warm. It unashamedly gets a little bit cold in winter and it gets a little bit warm in summer. We like living that way.”

There’s in-floor heating in the pods (beneath sisal carpet – another subtle reference to Queensland beach houses) that are used for a few days in the depths of winter, and a hardworking wood burner in the living area fuelled by fallen hardwood stockpiled when the site was sub-divided. In summer, when the living area is opened up fully to the north, shaded externally and screened (for security as well as protection from mozzies and flies), ceiling fans help with air circulation on the hottest days. Otherwise, the entire house warms and cools passively thanks to careful siting and window placement, dark cladding on the boxed rooms, extensive insulation, and lots of thermal mass.

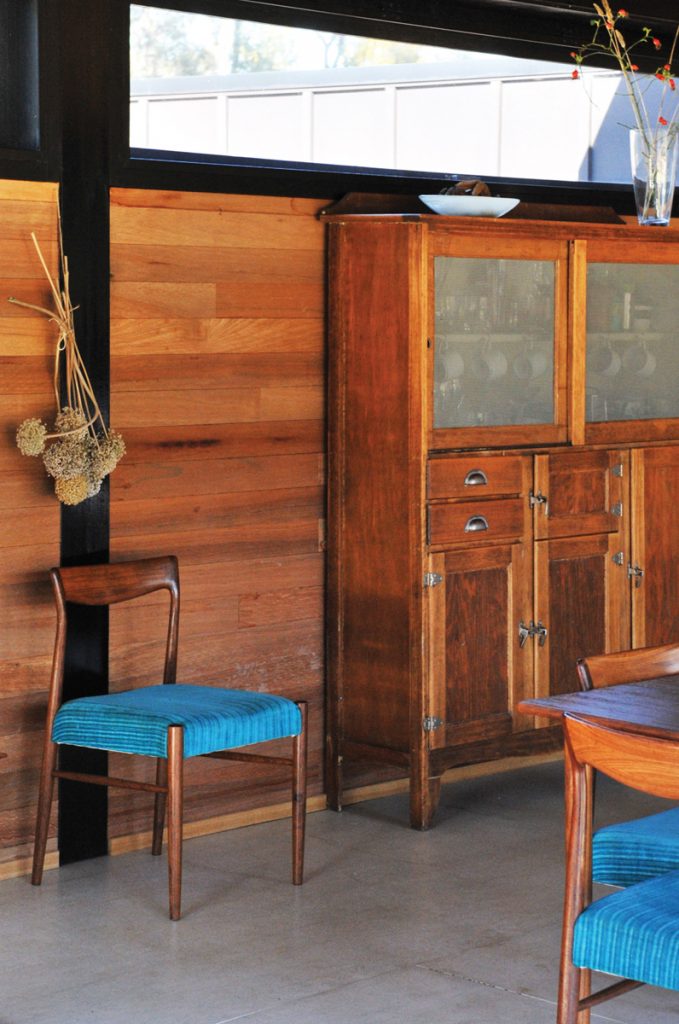

Working within a tight budget, Lucas designed a simple steel structure that could be installed by the manufacturer, allowing him as builder simply to fill in the gaps, piece by piece, over time, using the cheapest materials he could find. The pitched roof is lined in black melamine, the bathroom and ensuite tiled in cream “bricks” from Bunnings (given added interest with appealing, chocolate- coloured grout), and the kitchen’s distinctive timber island bench was picked up for a song on eBay.

Lucas never intended to line the walls with timber but when his eBay contact offered him some free timber salvaged after her house burnt down, he jumped at the offer. He’s pleased with the warmth it lends the interior and grateful for freebies that allowed him to afford bigger ticket items including the copper roof, which will age beautifully over time, extensive screening, which allows the openness in summer that he and Naomi craved, and a waste-water treatment worm farm located beneath the north-facing garden lawn.

“I’ve done this house in the complete opposite (way) to how I normally work,” Lucas says of the organic approach he took to the fit-out. Working with clients and builders he fastidiously documents everything upfront. “With this house I’ve done two or three drawings to get the building permit. If you strip the lining off these walls nearly every bit of timber has got a detailed sketch on it, because it was literally me out here working out how I was going to put things together.” Fittingly, the open, flexible approach reminds him of his time up north. “This was a very different process for us, and in fact it was more akin to what we were doing in Brisbane.”

The house was recently short-listed for a Houses Award and is garnering more attention than its owners ever expected. Not bad for a design that began as a “nice shed” and was constructed “on the cheap” to unashamedly experience the elements.

Specs

Architect

Lucas Hodgens of e+ architecture eplusarchitecture.com.au

Builder

Lucas Hodgens

Passive energy design

The house is oriented north with a 9-metre-wide opening to the main living area. In winter, stacking doors (full-height, inert, gas-filled and double-glazed) remain closed, and short eaves allow full sun penetration. Thick woollen curtains can be drawn across at night. In summer, doors are stacked back into a recess to create a full 9-metre-wide opening. Powder-coated stainless steel mesh screens stack across to provide security, protection from insects and fire protection. External venetian blinds can also be dropped down to block out the worst of the summer sun. Windows and doors are positioned and sized for effective cross-breezes. Each room has a high level slot window and, on the opposite side, a full-height opening. This size differential creates a pressure change that assists air movement and night purging, maximising cross ventilation. Ceiling fans assist further. A wood fire utilises fallen Ironbark and Yellow Box salvaged from the sub-division of the land. Solar panels compensate for under-carpet heating. Dark cladding assists in keeping the house warm in winter. All water recycled on site. The design provides comfortable living with low energy use year round.

Materials

The bedrooms use concrete slabs on the ground for thermal mass. The sisal floor covering used in bedrooms is a natural woven fibre made from the agave plant.

The elevated living pavilion uses a suspended steel floor with a layer of structural flooring and compressed 15-millimetre cement sheet finishing board that provides some thermal mass.

All roofs and walls are of highly insulated, lightweight construction. The interiors feature expressed laminate panels and recycled timber cladding and the external skin is clad in painted cement sheet cladding with timber cover strips. Windows and doors are aluminium framed with double glazing and comfort glass.

Roofing

Copper has been used for all exposed roofing and downpipes. This will weather and reflect the site conditions in which it sits.

Insulation

The roof is insulated with Bradford Gold High Performance R4.0, glass wool thermal. Walls are high density R2.5 glass wool thermal. The floors are insulated with R2.0 glass wool thermal.

Glazing

The house features aluminium-framed, double- glazed windows and doors. Breezway louvres and Viridian Comfort glass are used on the high-level windows.

Heating and cooling

Passive solar design features including northern orientation, external shading and effective cross ventilation, reduce the need for heating and cooling devices. In winter extra heat is provided by a wood heater and under-carpet heating in the bedrooms. Ceiling fans in the living areas are the sole form of mechanical cooling.

Hot water system

Hot water is provided by an Ecosmart solar hot water system.

Water

Rainwater is recycled using 23,000-litre tanks. A Biolytix worm farm in a septic tank allows waste to be converted to castings, filtered clean and irrigated on site. The Biolytix system is also very low on power consumption and maintenance needs.

Lighting

Lighting is generally hidden, allowing the use of efficient compact fluorescents. Where lighting is exposed as a feature, a naked bulb-type fitting is used.