Salvage And Share

Kat Lavers demonstrates the power of permaculture with the transformation of her compact Northcote garden, the Plummery.

Kat Lavers began her personal permaculture journey just three years before moving to Northcote in 2009, yet her compact garden – known affectionately as the Plummery for its productive plum tree – already yields 350 kilograms of produce a year. “There’s still plenty of undeveloped space,” said Lavers. “So still a long way to go.”

Prior to its permaculture-inspired life, Lavers’ garden was a jungle of weeds, contaminated soil, and brushtail possums. And the latter were wily adaptors, with appetites that swelled with garden yields. “Eventually [the possums] learned to rip nets and ringbark trees,” said Lavers. “I’ve now installed a Pingg-String electric wire around the fence, which has so far – fingers-crossed – been a successful barrier.”

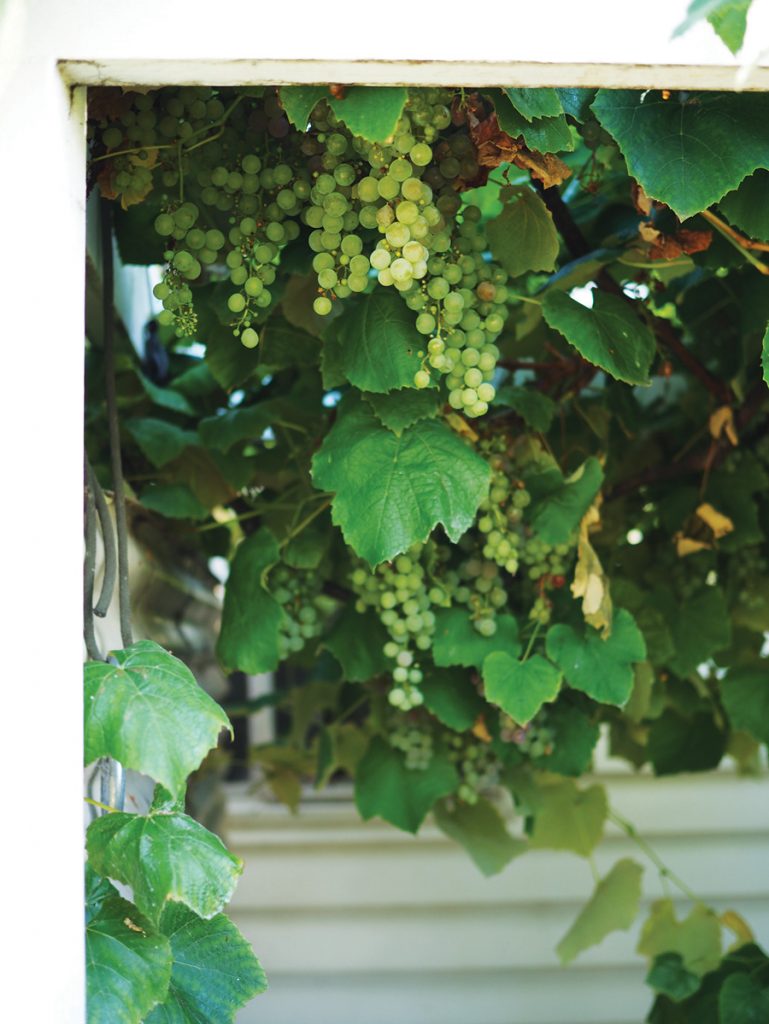

Today, located behind a rack of five or six bicycles and an unassuming weatherboard, the Plummery is a surprising Eden of exotic and familiar produce, including tropical fruit, delicately flavoured rocket, heirloom hops and grapes, fat spotty beans and speckled eggs.

The now sought-after permaculture consultant and program coordinator also inherited soil with unsafe lead levels: “A legacy of leaded petrol, [old lead-based] paint and industry.” So she installed raised beds filled with clean soil and things like leafy greens, tomatoes, beans and herbs. In the rest of the garden, the permaculturist only plants varieties, like fruit trees, which tend to draw lead into their non-edible parts.

Quail were chosen, instead of chooks, because they scratch less and are happy in smaller spaces with thinner layers of dirt, so could be isolated from the original soil. The latter is constantly being improved with homegrown compost, while the quail reliably provide a dozen eggs a week, and a steady supply of potent compost fuel.

Lavers describes her gardening approach as local, low-tech and salvage-where-possible. “If you walk into a nursery or hardware store you could be forgiven for thinking gardening is an expensive hobby.” But Lavers believes it just doesn’t have to be that way.

“I collect enough leaves from street trees in autumn to supply mulch and compost materials year-round,” said Lavers, who plants varieties with nectary flowers to attract predatory insects that tackle aphids. Seeds are kept to save money and produce stronger plants that become better adapted to the garden’s particular microclimate over time.

Multifunction is another important principle. “I like using productive trees and vines that also shelter my home from the sun and wind,” said Lavers. “Or combining a worm farm with a bench seat to save space.” In the same spirit, what might have been a dead space beside the house now houses a quail pen and a water tank.

Lavers is quick to point out that, as a system for creating sustainable human habitats, permaculture is relevant to many parts of our lives. “It’s often misconstrued as specific to organic or forest gardening techniques,” said Lavers. “But, in reality, permaculture is simply a design approach. So it applies as much to the way I plan my teaching classes as it does to the arrangement of plants in my garden.”

Not only clever and efficient, Lavers’ garden is a thing of beauty with its screens of tangled vines, persimmon and Chinese quince trees, as well as rattlesnake beans, motley tomatoes, and sprays of seeding parsley.

The grapevine, originally from North America, is said to have travelled from Italy to a Hepburn Springs pasta factory. Later, cuttings were passed on to the nearby Melliodora permaculture site, and then shared with Lavers a few years ago.

In all, the Plummery is proof of permaculture’s power to transform, beautify and abundantly nourish – without costly and environmentally dubious products. And, coupled with its practitioners’ inclination to share seeds, cuttings and excess produce, it is also a lovely connecting force.